Staffing and quality

Issues related to staffing and scheduling, such as wages, overtime, attendance, training, employee turnover and recruitment, have all been hot topics in aging services in recent years. They play critical roles in safety, risk, and quality. In conducting, facilitating and reviewing root-cause analyses of adverse events in various healthcare settings, ECRI Institute has identified staffing and scheduling issues as a frequent contributing factor or root cause. The implementation of payroll-based journal reporting shows that the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services is aware of these relationships as well.

So what is the connection between staffing and scheduling on the one hand, and safety, risk and quality on the other? Perhaps it’s that staffing problems can lead to a multitude of potentially dangerous conditions within an organization, including poor morale, diminished job satisfaction, high turnover and a lack of team cohesion—all of which lead to performance gaps in the delivery of services. At minimum, staffing and scheduling problems act as “noise,” creating dangerous distractions and interruptions in the delivery of care and services. In severe cases, problems rooted in these areas lead to competing priorities, forcing difficult and often no-win decisions about what gets completed and what does not.

It stands to reason that if ineffective staffing and scheduling create instability, then effective staffing and scheduling can be a powerful force that brings stability and resilience into care and service delivery environments. In aging services, quality and continuity of care is nearly impossible to achieve without continuity in:

- Staffing (having the right number of people with the right skills to match patient and resident workload) and

- Scheduling (having those people consistently at work or available for back-up at the right time of the day, week, and year).

To address these issues, organizations need to take a systems approach to staffing and scheduling. Staffing and Scheduling in Aging Services: A Systems REThinking Approach, a white paper available from ECRI Institute, presents an example of such an approach, called responsive staffing. Responsive staffing is a staffing and scheduling system that is both stable and flexible and that responds to the organization’s needs, as determined through analysis and critical thinking, over a 24-hour day and a 365-day year.

Do you have a staffing and scheduling problem?

Staffing and scheduling programs that do not respond to the real needs of residents and the organization can spur a host of interrelated problems that can in turn lead to adverse events, quality problems, or other challenges. Examples of these interrelated problems include the following:

- No-win situations, such as staffing–workload conflicts, task–timing conflicts, and task–priority conflicts

- Strain on employees, leading to burnout, fatigue, frustration, poor morale, job dissatisfaction and turnover

- Disruptions and distractions that occur when staffing is inadequate or cannot flex to meet workload demands

- Poor team cohesiveness, which in turn can adversely affect decision making, communication, problem solving, task completion, organizational learning and performance improvement

- Fragmentation of care and services, which can undermine continuity of care and foster incident-prone environments

- Rigidity in staffing and scheduling, which can push the system past the breaking point, particularly when nonroutine or unpredictable events occur

- Instability, such as on weekends, when heavy reliance on agency and per diem staff makes unfamiliarity with residents or current organizational procedures the norm rather than the exception

- Erosion of organizational staffing goals and policies under the push to “just get the schedule filled”

- Redirection of resources toward recruiting, hiring, training, creating schedules and managing scheduling gaps and away from resident care

Defining the problem by asking the right questions

“Does my organization’s staffing and scheduling program contribute to an internal environment that inhibits the likelihood of incidents or one that proliferates them?” Answering that question is an important start in designing an effective staffing and scheduling program by helping to clearly identify problems. Defining the problem in terms of environments, structures, processes, and functions can help us to better understand the issues that we face and create better strategies for improvement.

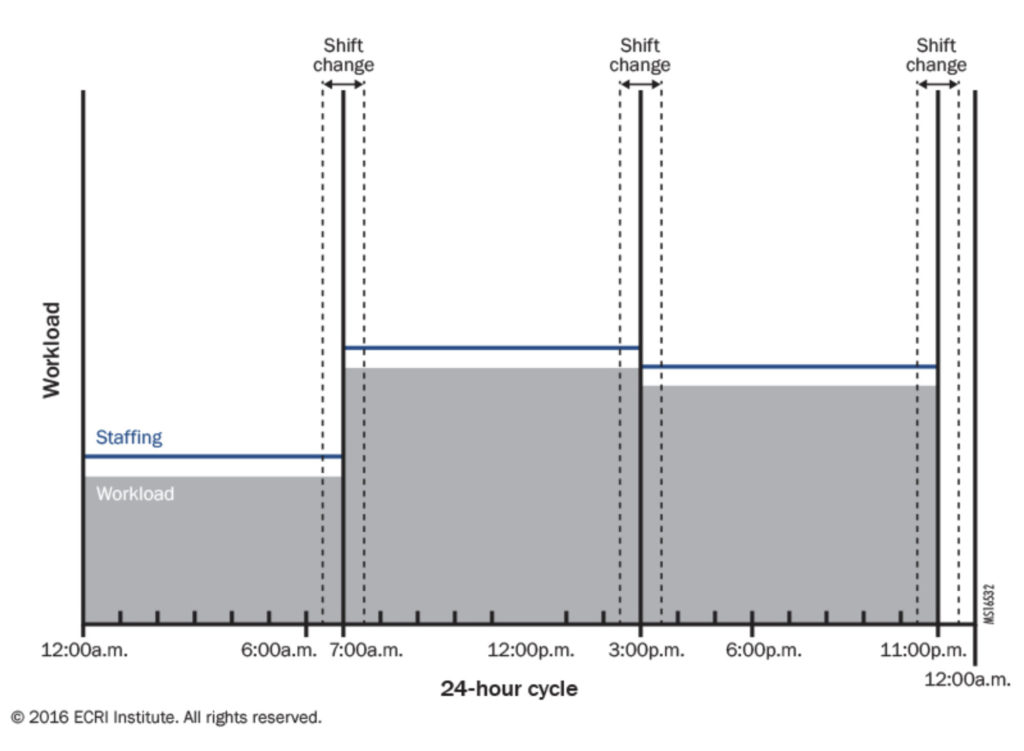

To do this correctly, we need to first be aware how we visualize staffing and scheduling and avoid the temptation to treat staffing, scheduling, and workload as static. “Fig. 1: Static Paradigm of Staffing and Workload” illustrates how we usually envision workload—namely, as being static throughout each shift.

Fig 1: Static paradigm of staffing and workload

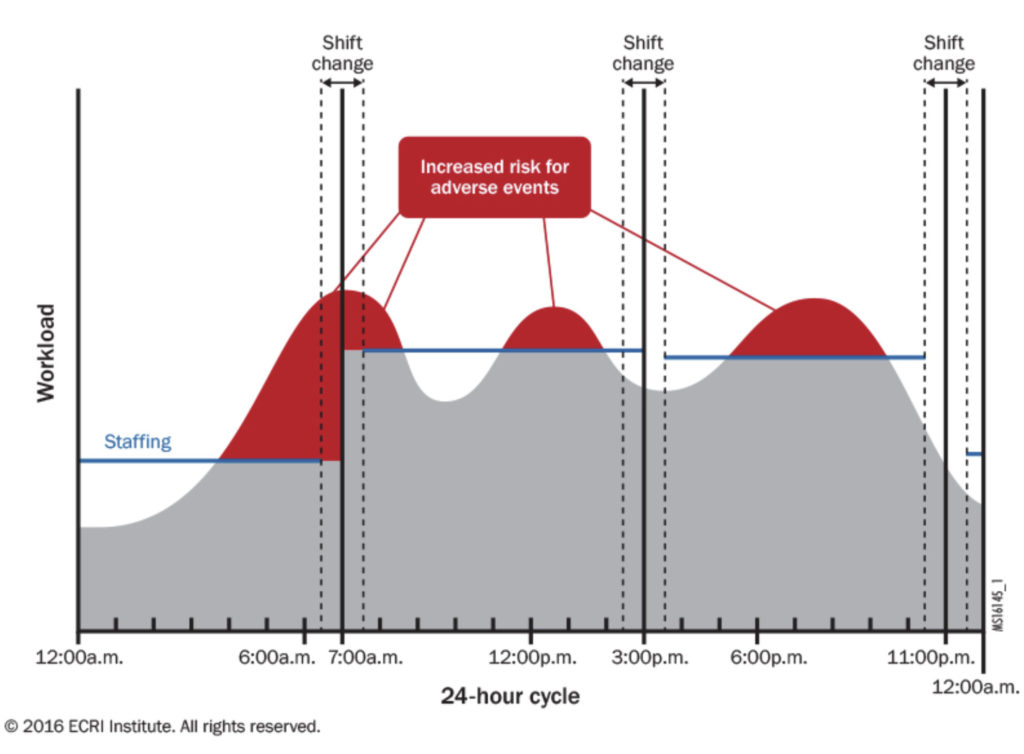

When we think of staffing and workload in such a static manner, the programs we create often have inherent flaws, because they cannot always respond to the realities of organizational life. “Fig. 2: Workload and Staffing over 24 Hours, as Imagined” shows that peaks in workload for recurring, predictable tasks, such as those surrounding morning activities of daily living and mealtimes, can raise the risk for adverse events if staffing and scheduling do not flex to meet workload fluctuations. Shift environments can also vary from shift to shift and day to day. Therefore, a solution that addresses a problem in one shift environment might not address a problem that exists in another shift environment, although it may be related or influence the other.

Fig. 2: Workload and staffing over 24 hours, as imagined

But even Fig. 2 does not always represent reality. What happens on an individual shift if, for example, a staff member calls out, many admissions occur, or an adverse event requires multiple staff members to respond?

This is precisely what makes staffing and scheduling processes so difficult to design and so important at the same time—staffing and scheduling programs must be responsive to very dynamic environments that have staffing needs, scheduling needs, and workloads that fluctuate between and within shifts. To be effective, staffing and scheduling programs must be capable of responding to these changing workloads, needs, and events in a timely way.

A systems approach

A systems approach to staffing and scheduling is one that is custom-designed. Responsive staffing helps organizations understand how to evaluate their needs and the needs of their residents, patients, and staff and how to design the system to respond to those unique needs.

Responsive staffing involves:

- Mapping peaks and valleys of workloads on every shift

- Determining what skills are needed and when and where they are needed

- Designing the system to respond to those needs

- Building in both stability and flex

- Continually monitoring performance indicators

Redesigning the system when things change (and they will)

One component of responsive staffing is organizational design, which holds that systems behave how they are designed. It refers to the process of analyzing the work that needs to be completed to achieve the goals and objectives of the team and organizing the workforce by positions and assignments to complete the workload. Analyzing workloads, positions, and team capabilities allows identification of periods when workloads demands can safely be accomplished by staff on duty, periods when there may be more staff on duty than workload demands or vice versa. This information can help organizations problem-solve and undertake changes, such as adjustments to workloads, organizational design, and staffing and scheduling.

But systems thinking goes beyond work design alone, accounting for other key organizational processes, such as communication, problem solving, training and growth, and evaluation and rewards. A systems approach acknowledges that there are changes in work design throughout the system throughout the 24-hour care and service delivery cycle. It also considers the work of those who are directly responsible for the production and delivery of services, as well as those who support the various departments. In other words, the importance of staffing and scheduling extends to all service departments and does not start and stop with direct care.

In fact, systems thinking concerns itself with how all parts of the system are integrated. When taking a systems approach to staffing and scheduling, organizations might examine elements including:

- Master schedules

- Scheduling positions and authority

- Employee status mix

- Work design and structure

- Shift change and weekend coverage

Ultimately, effective staffing and scheduling programs go far beyond staffing ratios. By creating an environment that either inhibits or proliferates adverse events and quality problems, staffing and scheduling directly affect the organization’s mission, reputation, and bottom line. In an industry that primarily involves people caring for people, they are fundamental.

Victor Lane Rose, MBA, NHA, CPASRM, is operations manager of patient safety, risk and quality-aging services, ECRI Institute. He is one of the authors of the Institute’s white paper on staffing and scheduling in aging services, the full version of which can be read at www.ecri.org/staffing. He can be reached at vrose@ecri.org.

Victor Lane Rose, MBA, NHA, CPASRM, is operations manager of patient safety, risk and quality-aging services, ECRI Institute. He is one of the authors of the Institute’s white paper on staffing and scheduling in aging services, the full version of which can be read at www.ecri.org/staffing. He can be reached at vrose@ecri.org.

I Advance Senior Care is the industry-leading source for practical, in-depth, business-building, and resident care information for owners, executives, administrators, and directors of nursing at assisted living communities, skilled nursing facilities, post-acute facilities, and continuing care retirement communities. The I Advance Senior Care editorial team and industry experts provide market analysis, strategic direction, policy commentary, clinical best-practices, business management, and technology breakthroughs.

I Advance Senior Care is part of the Institute for the Advancement of Senior Care and published by Plain-English Health Care.

Related Articles

Topics: Articles , Executive Leadership , Facility management , Staffing