‘Active agers’ drive new design model

Often, basic approaches in architecture and interior design develop incrementally in a given sector—with changes barely perceptible over time. But on rare occasions, both disciplines must take a quantum leap to a fundamentally new model—usually in the face of major new market realities.

We face such a watershed moment today in the senior living sector. And, speaking from experience, those who adapt to the new era wisely will enjoy success for several decades to come. It has been the good fortune for both my co-author Rocky Berg and me to arrive at the edge of a new era in design earlier in our careers—and to have the privilege of influencing basic design models.

For me, it was in the hospitality industry. I was the design architect on The Mansion on Turtle Creek in Dallas, whose design was influential in creating the boutique model of hospitality that took root in the ’80s—and continues to flourish today. For Rocky, it was in the senior living industry. During the ’90s, Rocky led our design effort on a bold new vision for independent living combined with a continuum of care and stylish living. The result was Edgemere in Dallas—now widely recognized as a prime template for resort-style senior living.

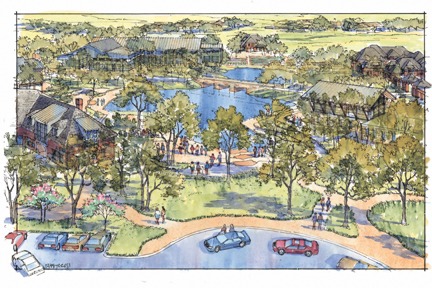

|

Figure 1. The new design model dissolves the "walls" associated with CCRCs. Photo courtesy of three: living architecture. |

Ironically, the new era we face in senior living design can best be described as a fusion of boutique hospitality and independent-oriented senior living. The result is an “active aging” design model that

offers a clean departure from any existing models. This new mode—which we have coined “living architecture”—is predicated on a dramatically shifting new social landscape that demands lifestyle resources that move in sync with active lives in motion—and their exacting expectations.

THE NEW SENIORS

Before I share specifics on how living architecture looks and feels, let me point out what it must achieve. Fundamentally, it must address a number of new design imperatives being driven by a demographic tidal wave that includes both the boomers—who began to hit 65 in 2011—and what we call the “proto boomers”—those Americans now reaching 75, who have largely the same expectations. Like the boomers, the proto boomers are still mostly fit and active—and intend to stay that way. Collectively, some refer to this segment of the senior population as “active agers.”

Active agers go mainstream. The number of Americans considered by some as “seniors” between the ages 60-75 is now one of the largest population blocks in America—with the boomer “bulge” continuing to feed it. This means that aging Americans are no longer the declining demographic on the margins of the mainstream—they are the mainstream. They determine their environment—and no one else.

Not surprisingly, active agers insist on services shaped to them rather than shaping their lives to the institution in terms of items such as meal choices, healthcare and engagement with the broader community. For the first time, aging won’t equal exile, however elegant, to the margins of mainstream society. It means an extended active and productive life, lived in the nexus of the larger society. Community integration and engagement is the new design mantra. Communities will become inclusive living environments, instead of islands of exclusivity.

Retirement is obsolete. “Saving our society” is back. A second new reality is that most aging Americans no longer anticipate retiring in the sense of ceasing to be productive and earning money. They simply can’t afford to and, in many cases, prefer to pursue the boomer ideal of unending personal growth and relevance. They will need a living platform designed for both ongoing productivity and personal expression.

Healthcare as individual as your thumbprint. Because of advanced new medicines, technologies and wider access to healthcare, active agers will become the most long-lived older demographic group in history—many achieving the century mark. Although they will still need much of the healthcare associated with advancing age, they will require and demand it in ways more tailored around their individual lifestyles and body types. Bundling of health services is now very “last century.”

DESIGN FOR ACTIVE AGING

Living architecture equals transformative experience.It begins by bringing in the best of world-class hospitality design into the mix. This sector has nearly perfected the user experience into a personally transformative experience of personal renewal. In fact, the people who are choosing this level of service while traveling will be the very people who will become the senior residents of tomorrow. They will look for an unbroken level of service.

For example, the residents will be called—and considered—“guests,” and will live in housing that more resembles a four- or five-star hotel than a typical continuing care retirement community (CCRC) of today. Whether in a high-rise or lower level building, the rooms and amenities will be built around the consumer experience rather than an institutional economy of scale.

The human element will be likewise transformed, with community staff tuned to ensure that every guest’s need is met including room service, pet walking, newspaper delivery to their door and personal laundry service. Design will affirm this ethos at each step, underscoring that the community is an extension of the guest, not vice versa.

The focus will be on individualization across the board including healthcare, food and beverage and amenities. This freedom will stem from a decentralization of these assets in favor of a model that integrates a range of outside sources to complement those that are incorporated in the community.

Some of these outside resources will be physically interspersed within the community’s campus, and could include outside retail outlets for wellness, education, civic food and shopping—and even extensions of local hospitals and colleges, or at least close proximity to their campuses (figure 1).

This design-driven mixing of ages will keep guests very much in the mainstream of culture and current trends and attitudes. This becomes a wellness and longevity factor as well, since the research says staying socially connected is vital to health and productivity.

|

Figure 2. A creative use of functional space incorporates multipurpose and multisensory experiences. Photo courtesy of three: living architecture. |

Within the community itself, design choices will create much more efficient use of space while enhancing the guest experience. Rather than spaces being defined by function, such as a meeting room being only and always a meeting room, the architecture itself will transform that space into multifunction spaces—merging multisensory experiences into a single space.

For example, a space might have an open desk or table surfaces for group meetings but also include a kitchen or bar station in the same area. This “mash up” of activities allows more active use of functional space and injects a higher level of energy and mental engagement (figure 2).

Hospitality-driven design innovation will permeate every inch of the living community. In guest rooms, furniture and closets will have built-ins to make maximum use of available space, rather than having to retrofit furniture from a previous house that claims an extra foot or two of clearanceand is completely unnecessary.

The kitchen will be more compact—functional, but wonderfully styled and integrated into the living space. Bathrooms will be spacious, tailored and stylish with a feel associated with luxury hotels as opposed to the institutional offerings of today's properties.

While a bold fresh vision, the good news is that this new model will allow developers to remain—or become—viable despite a down economy because it is shaped for the future, starting today. The really good news is that some of its elements can—and are—being retrofitted into existing communities, making them attractive to boomers and thereby extending the life of the community for the next 25 years, as active agers reshape the “second half” of how Americans live.

Gary Koerner is founder and principal of three: living architecture, based in Dallas. He has been involved in design solutions for the hospitality industry and works with the senior living design group at three-living architecture, which is headed by Rockland (Rocky) Berg, also a principal at three: living architecture. For more information go to www.threearch.com.

I Advance Senior Care is the industry-leading source for practical, in-depth, business-building, and resident care information for owners, executives, administrators, and directors of nursing at assisted living communities, skilled nursing facilities, post-acute facilities, and continuing care retirement communities. The I Advance Senior Care editorial team and industry experts provide market analysis, strategic direction, policy commentary, clinical best-practices, business management, and technology breakthroughs.

I Advance Senior Care is part of the Institute for the Advancement of Senior Care and published by Plain-English Health Care.

Related Articles

Topics: Articles , Design